Meditations and Musings on Foot-washing

Please read these with care and attention. Let them linger and then bring your responses to our next Southpoint Central or, if you have the courage post your responses on this web site, do so in the comments.

Thanks for having the courage to enter in the challenging reality and truth of this hard to apply message.

Brent

Stinky Feet and Justice

distributed 4/14/06 – ©2006

In some Christian traditions, worship on Maundy Thursday includes a foot washing ritual. I have talked with people who have found rich meaning in this liturgical event. They tell me that it is humbling, and a striking expression of community.

As I study the account of Jesus washing the feet of the disciples (John 13), though, I’m starting to see that what Jesus did at the Last Supper has far more radical implications than any of us are likely to experience in church. When we come to the occasion knowing what will happen — and when all involved have thoroughly scrubbed their own tootsies in advance — the stunning impact of the first event isn’t there.

Try to imagine the original context. People of the time wore sandals, and the streets were full of camel dung, donkey urine, and various kinds of rotting garbage. Everybody had filthy feet. When entering a home, any person with manners would remove their sandals and wash his or her own feet. Sometimes — as a sign of incredible hospitality — a servant or a member of the household might perform the foot washing.

I’m hard pressed to think of a routine activity today which is at once so intimate and so demeaning. Foot washing is in the range of emptying bedpans in the nursing home.

There are things having to do with personal sanitation that you’ll do for yourself, but which you would never ask your friends or neighbors to do for you. And you would never, ever make such a request of someone that you hold in high esteem.

In fact, I don’t believe that those folk in biblical times really “made a request” for someone to wash their feet. That’s not something you ask a person to do as a favor. You instruct them to do it from a position of authority. “Our guests have arrived. Wash their feet, then clean the stable. Let me know when you’re done.”

Foot washing was an act that took away all the washer’s dignity and status. It was among the worst of all possible tasks, and deserved special mention beyond all other everyday activities. A Jewish midrash on Exodus says that the washing of a master’s feet could not be required of a Jewish slave. In 1 Timothy 5:10, a worthy widow is described as one who has “shown hospitality, washed the saints’ feet, helped the afflicted, and devoted herself to doing good in every way.” As a dramatic sign of ultimate devotion, a student might wash his teacher’s feet.

It is hard for me to internalize the social context and the layers of meaning that were related to foot washing. If you were fortunate enough to not have to wash your own feet, the job would invariably be done by someone of a lower class or status. Those daily dynamics of power and servility are outside of my experience.

In the modern, churchy, ritual of foot washing, we come together as friends and as peers. The one being washed cares about the experience and reactions of the washer, and is embarrassed if their own feet smell. Long ago, though, the servility of the traditional role allowed the one being washed to know full well that their feet were gross, and not care what the servant thought. It was their job to do such things.

What Jesus did on the night of the Last Supper is steeped in his society’s routine experiences of power dynamics. The disciples were bickering constantly among themselves about who was the greatest. On that last night, to slam home a message that they could not forget, Jesus taught them with his actions.

The act of washing the disciple’s feet demolishes the entire notion of status and privilege. It invalidates any consideration of “greatness.” It turns around the question about “who will admire me and serve me and meet my needs?” It asks instead, “who must I acknowledge, and how can I meet their needs?” It turns “what’s in it for me?” to “what do I have to offer?”

Some churches do foot washing as a ritual. The challenge from Jesus is to make radical servanthood a way of life.

+ Â Â + Â Â + Â Â + Â Â +

Within religious circles, it is often said that the environmental distress of the world is, at its heart, a spiritual crisis. If we are to live in a just and sustainable way within a global community, we need a profound change in our self-understanding, in our deepest hopes and aspirations, and in the motivation for all of our relationships and behaviors.

The servant life of Jesus, symbolized so succinctly in the act of foot washing, shows us what that deep spiritual transformation looks like. And the horrified reaction of Peter shows us how radical that transformation really is.

The call of faithful servanthood is far deeper than being helpful or kind. We are called to discard all of our aspirations for prestige and privilege. We are to find our life’s meaning in the service of God, of our community, and the web of life.

The Jesus who picked up a basin and a towel to wash the feet of his disciples is rebuking every way in which we accept inequality, and every way in which we live with assumptions of privilege. For those of us who live within the luxury and dominance of the modern consumer class, our entire way of life is challenged.

When we hesitate to forego any of our luxury for the sake of our sisters and brothers who live in the most destitute poverty — 1/6 of the world’s people live on a dollar a day or less — then we are not getting the notion of servant lives. When we find it impossible to imagine a way of life that is ecologically sustainable, because we can’t conceive of living without our gadgets and conveniences and our status, then we don’t understand the challenging message of Jesus.

On the last night of his life, when he tried to get the core of his entire message across to his disciples, Jesus washed their feet.

On this most holy weekend of the church year, may we grapple with the full challenge of that simple act.

Shalom! Â Peter Sawtell

Executive Director

Eco-Justice Ministries

Anonymous Blog Entry

Friday, April 10th, 2009

Last night I washed my feet.  I mean, I had my feet washed. Well, actually I did both. First I washed my feet; then I went to church and had my feet washed. I also flossed my teeth and took a shower. I bet if Peter had known what was in store for him at the Passover meal, i.e. the Last Supper, he would have done exactly the same thing.

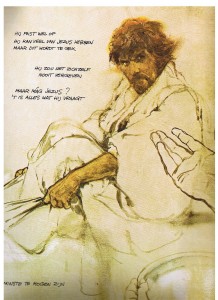

What an embarrassment to have someone (especially when the someone is Jesus—his Lord, his Christ) hold your grimy, smelly old feet in his hands. Peter says to Jesus,  ”Lord, are you going to wash my feet?” Jesus replied, “You do not realize now what I am doing, but later you will understand.” “No,” said Peter, “you shall never wash my feet.” Jesus answered, “Unless I wash you, you have no part with me.” (John 13:6-8 NIV)  Jesus, the Son of God, takes the role of a servant or even a slave.

Not only does Jesus show us our call to servanthood in the footwashing, but the footwashing is an intimate act of love. The first time I had my feet washed, I was overwhelmed by the luxurious feeling of being a beloved child in the parental hands of God. Who but a loving Father or Mother would take the time to tenderly caress and dry each little toe?

I wish I was brave enough to take my unwashed feet to church, but I’m not. It’s awkward enough for me to receive the gracious gesture of a stranger kneeling before my clean feet as servant and surrogate parent.

Lord, teach me to receive the ministries and love offered to me even in uncomfortable and humbling circumstances. But teach me also to serve with an unqualified, nuturing love. Amen.

No comments